Reviving Tangible Support from Female Civilian and Combatant Sectors Across the Sikh Panth

Reviving the Khalsa's Military Legacy Series: Part 2

“In 1915 leading personalities of Jatha had been arrested in connection with ‘Lahore Conspiracy case’. Warrants were also issued to arrest Bhai Surjan Singh Jee, husband of Bibi Joginder Kaur. A police party arrived in village Gujjarwal to search Bhai Surjan Singh’s house. However he was not present then. Bibi Joginder Kaur put a lock on her outer gate and stood on guard like a lioness. She warned the police party that they could not search in absence of her husband. She roared further, “Be warned and stay away! Any attempt to approach shall lead to serious consequences.” Blue turban adorning her head and a sword in hand, She presented an awe-inspiring personality. This discouraged the police from any action. The law also prevented search in absence of a male family member, but law was never cared for then or even now. It was only the bold challenge of Bibi Joginder Kaur that restrained the police. Many other houses had been searched in absence of male members. Only Bibi Joginder Kaur proved exception and worthy example of outstanding Sikh-lady. She faced police courageously and checked their nefarious activity.”

- Bhai Randhir Singh Singh in “Rangle Sajjan”

“On manifesting herself, she marched for war, like Bir Bhadra manifesting from Shiva. The battlefield was surrounded by her and she seemed moving like a roaring lion. (The demon-king) himself was in great anguish, while exhibiting his anger over the three worlds. Durga, being enraged, hath marched, holding her disc in her hand and raising her sword. There before her there were infuriated demons, she caught and knocked down the demons. Going within the forces of demons, she caught and knocked down the demons. She threw down by catching them from their hair and raising a tumult among their forces. She picked up mighty fighters by catching them with the corner of her bow and throwing them. In her fury, Kali hath done this in the battlefield. 41.”

- From Chandi di Var in Sri Dasam Granth Sahib

Since the militarization of the Panth in 1699, Sikhs of all ages and backgrounds have taken up arms to protect the Sikh faith. While the British colonial period saw a decline in this martial tradition, including restrictions like the Indian Arms Act of 1878, this spirit was reignited during the early 20th century, particularly with movements such as the Ghadarite movement. A line from one of the posters put up by Giani Harbhanjan Singh on January 8, 1915, at the gateposts of Khalsa High School, at the request of Bhai Sahib Bhai Randhir Singh, personifies the spirit of the time:

“Make preparation for mutiny soon; To destroy the rule of the tyrants, O People.”

This mix of bravery, courage, and revolutionary spirit ultimately led to the independence of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the Republic of India in 1947. However, the Sikh community and Sikh practices continued to be suppressed under the Indian government, with interference in various aspects. A resurgence of this fighting spirit was witnessed after the Saka of Amritsar in 1978, eventually evolving into the Dharam Yudh Morcha and Kharku Lehar, which were crushed by the Government of India, effectively ending around 1995. While there is a current resurgence of political activism in the Panth after the past four decades, a significant gap remains in the active, tangible support from women—both on the front lines and behind the scenes. Tangible support, as defined by the RAND Corporation, includes the ability to supply personnel, material, financing, intelligence, and sanctuary to fighters - all of which are vital to the success of any resistance movement.

This should not be confused with popular support, which is "the general approval, backing, or endorsement of a movement, cause, or group by the majority of the public or a specific population."

According to a study released by the RAND Corporation in 2010:

"Popular support was found to be an important contributor to insurgency outcomes. However, tangible support...was found to be even more important than popular support.

While popular support and tangible support often followed each other in the [20] cases studied—if the insurgents had the support of the population, they were able to meet their tangible support needs; if they lacked popular support, they were not—when popular support and tangible support diverged, victory followed tangible support."

In the case of Sikh resistance, tangible support includes both logistical assistance (such as supplying food, medical supplies, shelter, etc.) and active front-line participation. For example, during the Dharam Yudh Morcha and Kharku Lehar, tangible support took the form of underground networks that provided food, shelter, and medical aid to those involved in the Sangarsh. However, currently, women’s involvement in providing tangible support has been significantly lacking. This is concerning, as tangible support has historically been crucial to the success of resistance movements, as demonstrated by modern history. To ensure the effectiveness of such movements, it is essential that both men and women contribute. Sikh history offers valuable examples of the diverse forms of tangible support provided by Singhnia during the decline of the Mughal Empire and the rise of the Sikh Empire. Let’s explore these insights from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Civilian Women

Civilian (noun): ci·vil·ian | \sə-ˈvil-yən\

A person who is not on active duty in the armed services or part of a police or firefighting force.1

Just as today, when many individuals are not involved in the military, law enforcement, or similar fields, not everyone’s seva was carried out on the front lines. For some women during the 18th and 19th centuries, their seva took place at home—supporting their husbands in battle and nurturing their children to become the future defenders of dharam. While they may not have been on the front lines, their strength and resilience should not be underestimated.

George Thomas (1756–1802), an Irishman who led a couple of successful military campaigns in 18th-century India, observed the lives of Sikh housewives from the outside, labeling their situation as "unhappy."2 Even so, he could not help but take notice of their ability to physically confront danger when needed.

"Instances indeed, have not unfrequently occurred, in which they have actually taken up arms to defend their habitations, from the desultory attacks of the enemy, and throughout the contest, behaved themselves with an intrepidity of spirit highly praise-worthy.”

Zakariya Khan (d. 1745) also discovered the abilities of these ladies.

One day, he was informed by Moman Khan (one of his generals) that the town of Chavanda was empty of [Sikh] men, as they had left due to a wedding. He saw this as an opportunity to seize the town and set out with a strong force of men. The story3 continues:

“For hours the Singhnis resisted the Turks as a snake resists a mongoose. With determination and grit, Bahadur Singh's Singhni slew Khan's bravest warriors. What is time when the true lord hears your prayers? Did Ram fear the ten-headed Ravana? Did the youth Krishna fear the older Kansa? With blow after blow the Singhnis' broke the back of the Turks. Utterly dismayed Khan ordered a retreat and ran to his camp. Deserting Chavanda not a single Mughal was to be seen. Those who had dreamed of succulent women. Those whose eyes and loins had filled with lust, now cried in dismay. Blood lay pooled all around. Amongst it all stood Bahadur Singh's Singhni.

Hearing the success of the women of Chavanda, the Singhnia in Punjab were happy. Taking courage, many times did they battle the Turks. They knew well how to protect their honour, religion and their homes.”

These incidents indicate that, at the very least, the general Sikh female population possessed a familiarity with handling shastar. Dr. Maninder Singh Patiala, a Senior Research Scholar at Punjabi University Patiala, further emphasizes this point by noting that certain Sikh weapons, such as the katar, were specifically designed with women in mind (Video credit: Jaspreet Kaur - @jaspreet1843 on X).

Combatant Women

Combatant (noun): com·bat·ant | \kəm-ˈba-tənt\

One that is engaged in or ready to engage in combat.4

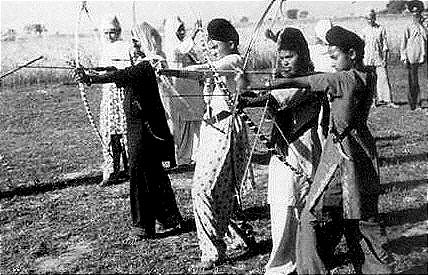

For the women who traveled with the Singhs, life among the two groups was similar. Both were armed, familiar with shastar vidya, and fought when necessary. Mai Bhago is probably the most well-known example. Being the daughter of Malo Shah, a member of Guru Hargobind Sahib’s army, she was trained in shastar vidya by her father. This martial education prepared her to lead a group of 40 warriors in the Battle of Muktsar in 1705, and afterward, she continued her life with Guru Gobind Singh, remaining shastardhari.

She wasn’t the only woman though.

Christian missionary Rev. J. Caldwell, a Presbyterian stationed in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, was accompanied by his wife, Mrs. Caldwell, and a native assistant named J. Gabriel.5 In the 1843 edition of the Foreign Missionary Chronicle, he described his encounter with a female Akali. The excerpt is as follows:

"We were visited this forenoon by a most singular character, and Akalin, or female faqir of a particular sect. Like the class of mendicants to whom she belongs, she was armed to the teeth. Over her shoulder was slung a sword, while her belt was graced with a large horse pistol, a dagger, and sundry other weapons of destruction. Another sword hung by her side. Her turban was ornamented with a panji and five or six chakkars. The panji is a horrid instrument made something in form of a tiger's claws, with five curved blades exceedingly sharp. The chakkar is a steel discus, of six or eight inches diametre, very sharp also, and no doubt a destructive weapon when hurled with sufficient force. She was, certainly, the most dangerous looking lady I ever saw...

It appeared by her own statement that she was a widow, and that her husband was an Akali; that after his death she had joined the sect and remained with them ever since. She had, she stated, been on a tor to the south of India, and had travelled a great deal since she had become a faqir."

Another foreigner, Major Robert Leech of England, encountered a group of Sikhs and described what he saw in his publication Notes on the Religion of the Sikhs and Other Sects Inhabiting the Punjab, published in 1845.

“They [the Akali Nihang Singhs] are the fanatics of the Sikh religion - literally covering themselves with iron, generally wearing, besides 2 swords at their side, from 1 to 7 quoits on their turbans which they make very high by means of a knife stuck in the centre, and an iron chain wound round. They stick 3 or 4 more knives in their turbans, and have generally a spear besides, several daggers in their waist-band. Their women are also armed like the men, and are said to be expert horsemen - and to be able to make good use of these arms when required.”

This account of the armed and formidable Sikh women is echoed by Gyani Gyan Singh, whose writings describe an encounter between a Sikh jatha and a group of Begums (female aristocrats) in the city of Delhi.

“Then they looked at the Singhnia. They took them into their palace. They [Singhnia] said, “Sat Siri Akal”. They replied “Salaam” and sat them down. Seeing their form and strong bodies. Dressed in armour and weapons. Listening to their conversation of plundering and war. And how to kill a hunt. And how to aim with bows and muskets. Hearing them, they were astonished.“

The Misl Period

Tangible support extends beyond battlefield participation; it also includes political involvement, which played a key role during the Misl period. Around 14 different women can be said to have contributed to the political landscape during the Misl period, but we will focus on three: Rani Sada Kaur, Mai Nakain, and Rani Sahib Kaur.

Rani Sada Kaur was the Chief of the Kanhaiya Misl from 1789 to 1821, a period marked by her strategic leadership and political acumen. Her influence was not limited to military engagements but extended deeply into the political realm, where she demonstrated remarkable foresight and insight. This was especially evident after the death of her husband, Gurbaksh Singh. As the leader of the Misl, she was not only tasked with maintaining its power but also with guiding it through challenging political landscapes.

“Gurbaksh Singh was now reposing in his grave, but in his widow, Sada Kaur, there survived a spirit of unusually keen political insight, resting on a broad foundation of personal intrepidity such as women have, from time to time, displayed in all ages and in all countries, when men have given them the chance. That was a glance of special wisdom and foresight which showed Sada Kaur, as she dreamed out her future from the midst of many present nightmares, that it was not given to the Kanhya Misl, good as its record of hard knocks and increasing influence had undoubtedly been, to take the lead among the Khalsa clans;….”6

Rani Sada Kaur played a crucial role in facilitating her eventual son-in-law Ranjit Singh’s rise to power by providing him with military support and strategic alliances. Her leadership was instrumental in the capture of Lahore in 1799, where her contingent helped Ranjit Singh secure the city, marking a decisive moment in his consolidation of power. This, along with the alliance formed through her daughter’s marriage to the Maharaja, strengthened Ranjit Singh's position and helped unify the Sikh Misls under his rule, leading to the establishment of the Sikh Empire. Despite the shifting tides of power, Rani Sada Kaur's influence remained undeniable, and her legacy continued to resonate in the political landscape of the time.

Similarly, another powerful woman, Datar Kaur (also known as Mai Nakain), played a pivotal role in shaping the course of Sikh history. She took control of the Sheikhupura Fort after her six-year-old son, Kharak Singh, had conquered it. In 1811, Maharaja Ranjit Singh officially granted her the jagir (deed) of Sheikhupura. Around this time, she began residing in the fort and even held her own court, demonstrating her influence and leadership.

Bibi Sahib Kaur, like Datar Kaur, was a leader whose contributions also significantly strengthened the Sikh Empire. In 1794, when her brother Sahib Singh, at just 14 years old, took control of Patiala state, he appointed her as chief minister, recognizing her leadership and ability to navigate the complexities of governance. That same year, when the Marathas advanced on Patiala, Bibi Sahib Kaur led the defense, defeating them and driving them back at Karnal.

“Sahib Singh, now aged 14, took the reins of state into his own hands, appointing his sister Sahib Kaur to be chief minister. In 1794 the Marathas again advanced on Patiala, but Sahib Kaur defeated them and drove them back on Karnal.”7

George Thomas had his own encounters with Bibi Sahib Kaur. In his memoirs, he describes her as a woman of courageous spirit, even more so than her brother.

“This lady, who we have before seen, had on several occasions exhibited a spirit superior to what could have been expected from her sex, and far more decided than her brother, now offered to take to the field in person.”8

Reflecting on this history and its relevance today, it is evident that the martial spirit—a natural expression of bravery and courage—must be nurtured among Sikhs of all genders, regardless of their proximity to the battlefield. Guru Gobind Singh Ji, upon hearing of Bibi Deep Kaur’s courageous defense against Mughal soldiers on her way to meet the Guru, encouraged women to embrace this spirit, inspiring the Sangat to follow suit.

“Listening to the bravery of that Goddess (Bibi Deep Kaur), the Guru greatly praised her to all Sikhs and gave her a dress of honour. He ordered the congregation to be like that Singhni. Like this, when the Guru heard of the stories full of bravery of four or five other Singhnia, the Guru was greatly pleased.”9

This belief is further emphasized in his incorporation of warrior figures like Durga, Gohraan Raae, and others in his bani, underscoring Guru Gobind Singh Ji’s unwavering faith in the strength and courage of the feminine.

Continuing the Legacy

Just as the Singhs and Singhnia of the past played pivotal roles in shaping the Sikh Panth, today, the Outpost carries forward this legacy by ensuring that the spirit of Sikh bravery continues, both on the front lines and behind the scenes. Following in their footsteps, we are dedicated to equipping both men and women to uphold the legacy of Sikh resistance, providing a space where everyone can contribute to the cause as leaders, strategists, and logistics coordinators. By offering the necessary tools, training, and guidance, the Outpost inspires a new generation to defend dharam, embodying the values of Sikh bravery and resilience.

Thank you to Bhagauti Consciousness for their contribution to this article. You can explore more of their work by clicking on their profiles below.

"Civilian," Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster

Military Memoirs of Mr. George Thomas (1805)

Gyani Gyan Singh, Navin Panth Prakash (1880)

"Combatant," Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster

The Foreign Missionary Chronicle, January 1847 edition.

Calcutta Review, Volumes 92-93 (1891).

The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Volume 20, Pardi to Pusad (1907)

Military Memoirs of Mr. George Thomas (1805)

Twarikh Guru Khalsa. Gyani Gyan Singh (1894)

Well done!

Great piece!